Last Friday after markets’ close, Moody’s Ratings downgraded the quality of U.S. debt, citing rising fiscal deficits and debt-service costs, exacerbated in recent years by higher interest rates. This marked the latest move in a gradual erosion of U.S. creditworthiness, first dinged by S&P in 2011 during the debt ceiling crisis. As a result, none of the “big three” credit rating agencies now awards the U.S. their highest mark.

While headline-grabbing, the lasting impact of this decision is largely immaterial. Though long-term debt dynamics remain precarious, today’s corporate investors searching for high-quality, deep, liquid, and dollar-denominated fixed income assets have few alternatives to Treasuries.

Understanding the Downgrade

Why downgrade now? Moody’s decision arrived against a backdrop of budget negotiations on Capitol Hill, where the GOP-led Congress is expected to pass legislation to extend (and expand) tax cuts enacted in the first Trump administration. Moody’s action note explains: “If the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is extended, which is our base case, it will add around $4 trillion to the federal fiscal primary (excluding interest payments) deficit over the next decade.”

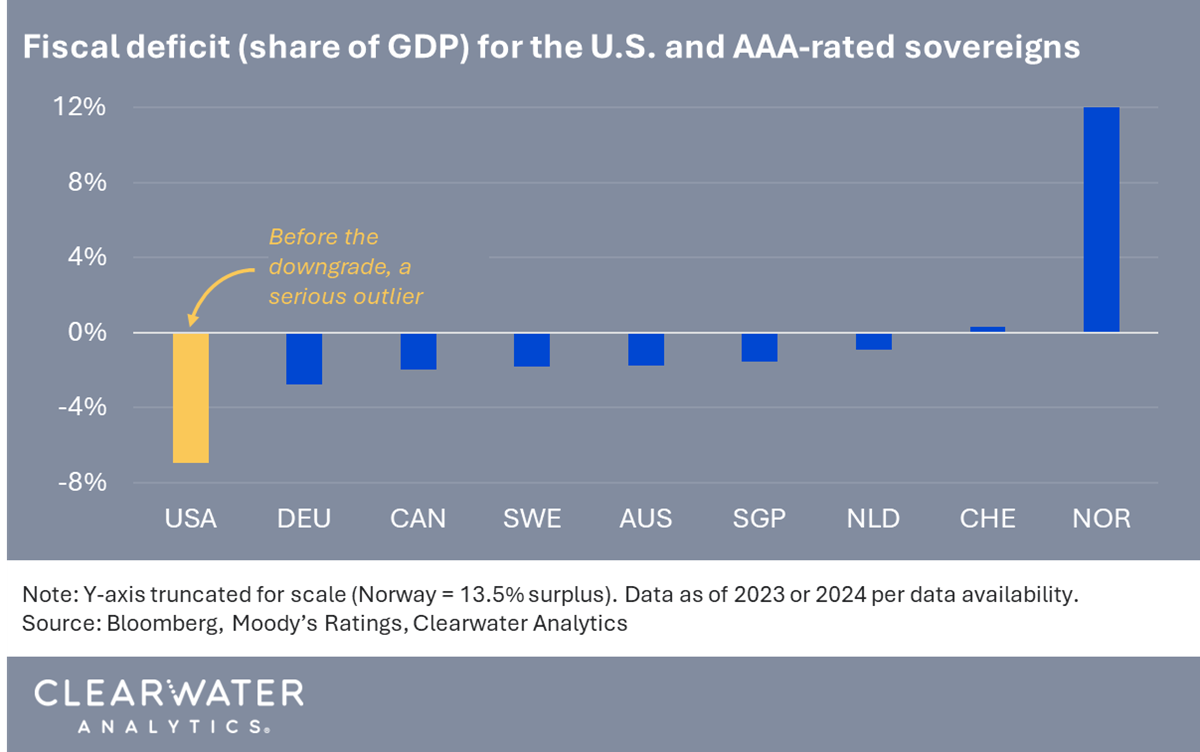

Moody’s downgrade is hardly a revelation. Reduced creditworthiness for the U.S. reflects persistent concerns over debt sustainability. Until Friday, the U.S. remained an outlier among other AAA-denominated sovereigns by running large deficits (see chart below).

It seems that 2025’s proposed changes to the fiscal outlook were finally a bridge too far. [Check out this quick primer on likely policy impact.]

Implications for the Macroeconomy: A Nothingburger with a Bad Aftertaste

With respect to the cycle, the downgrade will create few, if any, ripples across the broader economy. True, 30-year yields for U.S. debt are flirting with upper bounds not seen since before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Yet Moody’s alone is not driving large-scale market movements.

The rating decision reflects what bond markets were already pricing for: upwardly biased inflation (and, thus, higher rates), to a large degree spurred by debt-financed fiscal policy. Is U.S. debt “riskier” than yesterday? Not really. Should U.S. debt garner higher term premia (the compensation investors receive to hold longer-duration debt)? Over the long run, given Washington’s track record, probably.

What will influence cyclical conditions is the government’s tax plan. With rising deficits stoking the economy (such tax cuts confer purchasing power to consumers), price pressures

will be further tilted to the upside. As a result, monetary policy is likelier to remain in restrictive territory, a far cry from the 2010s, when the Federal Reserve was doing anything and everything to stimulate demand. Throw in tariffs—also stirring inflation—and the Fed will have its work cut out. Investors ditching cash should take note.

Implications for Corporate Investors: Treasuries Remain Treasured

For corporate investors, this week’s interest rate gyrations will have minimal impact beyond those with unusually long duration exposure. Where things get interesting are for firms with bylaws or investment mandates that require AAA-rated securities. Where will they turn?

The better question is rather where else can they turn? Their options are limited.

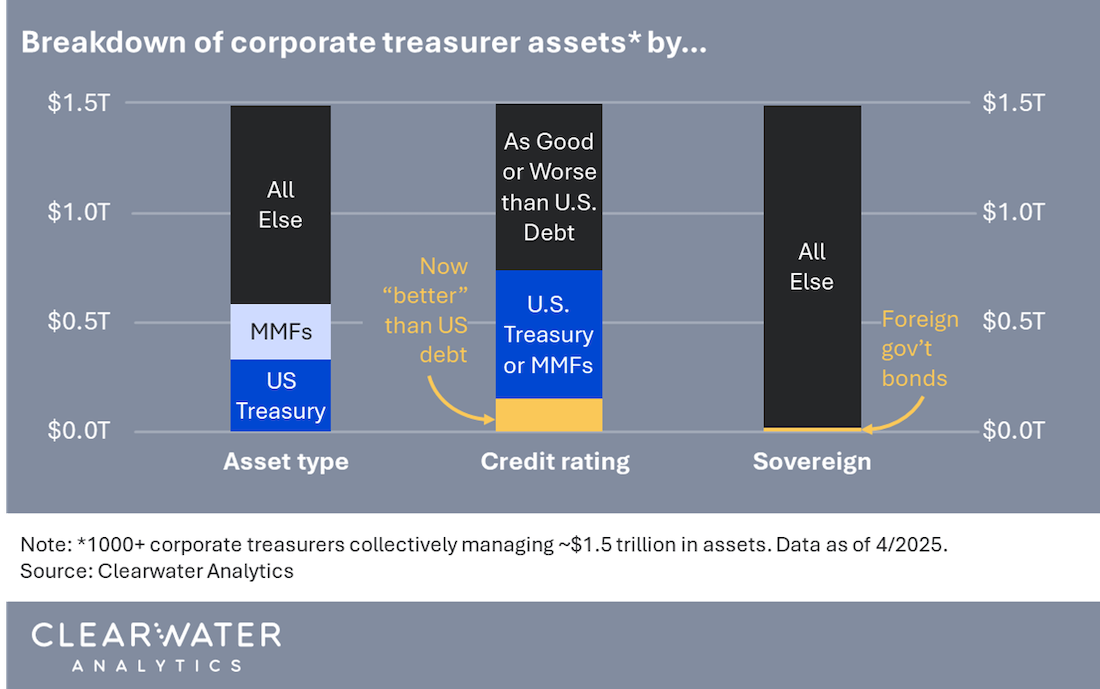

Clearwater’s data from 1000+ corporate treasurers with ~$1.5 trillion in combined assets shows the dominance of U.S. debt in portfolio allocation strategies. As of April 2025, direct holdings of U.S. Treasuries accounted for over 20% of firms’ total book value (see chart below, left bar). If we factor in short-term investment funds, which themselves have heavy Treasury exposure, this number nearly doubles. $600 billion is a lot of money to shift.

But what about investments that do meet AAA standards? At present, just 10% of book value within Clearwater’s database satisfies this criterion (see chart above, middle bar). Could firms searching for quality load up there instead?

Unlikely, given key differences in duration exposure. The modified duration for AAA holdings in Clearwater’s system (weighted according to book value) is .75, where the most common asset type is commercial paper. For Treasuries, excluding exposure via money-market funds, duration is 1.64. If firms want to pivot away from U.S. debt, they will likely have to sacrifice flexibility in duration strategy.

Finally, what about those countries still measured favorably by ratings agencies? Ignoring currency mismatch (a material assumption), we again run into the benefits of American sovereign debt: The U.S. Treasury market is colossal, nearly $30 trillion, approximately 10 times larger than Germany’s debt market, the next largest among highly rated sovereign debtors. With such size comes favorable qualities for investors, including but not limited to regularly scheduled auctions, depth, universal pricing benchmarks, global liquidity, and participation from a wide base of global investors.

At present, corporates have little appetite for foreign debt. International sovereign bonds comprise only 1% of total book value according to Clearwater’s system (see chart above, right bar). There’s certainly room to grow, but today’s minimal allocation suggests corporates have little desire or legal ability to do so.

In the Event of Turbulence, Treasuries Will Win Out

With the U.S. fiscal outlook under scrutiny, it bears noting that U.S. Treasuries remain the global standard for safe haven assets. Historically, Treasuries rally during periods of economic or market stress—such as the onset of COVID-19, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and, ironically, S&P’s downgrade of U.S. debt in 2011. This flight-to-quality dynamic underscores Treasuries’ unique position in global finance: no other asset combines safety, liquidity, and scale quite like U.S. debt . Even in a downgrade scenario, when global investors need refuge, Treasuries are the go-to choice.